Boating on the Nullarbor

1995

The Lake Boonderoo Expedition

‘Stony Country’

Meaning of the word ‘Boonderoo’ in the Western Australia aboriginal dialect Tjeraridja

IT’S AN ILL WIND THAT BLOWS NOBODY ANY GOOD

after Shakespeare, Henry IV

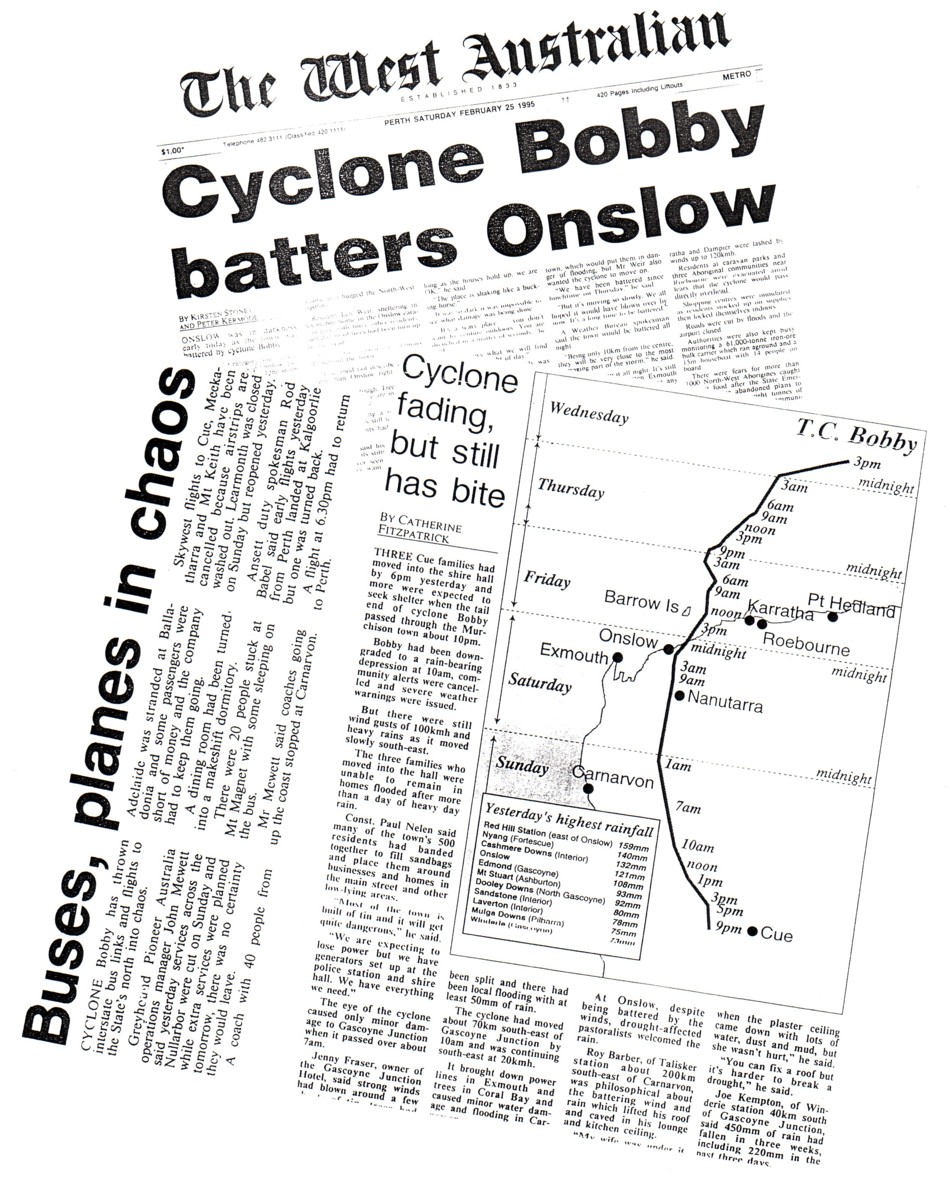

Cyclone Bobby smashed its way across Western Australia on 24 February 1995 and caused a great deal of damage. The accompanying rain caused floods through the eastern goldfields, inundated some mines and cut the Trans Australian Railway and Eyre Highway for many days. The result was many, many hundreds of thousands of dollars damage and loss to a wide section of the rural community.

But along with the problems came many benefits. The first, from our perspective. was the opportunity to do a history making trip through the Murchison Gorges which is recounted elsewhere on this site as No Wimps Allowed.

Cyclone Bobby affected a huge slice of the south-west of Australia. Normally dry lakes filled for the first time in many years, wildflowers were given as good a start as they could possibly have, the country was carpeted in green, the thirst of the pastoral regions and the outback was slaked and lasted for some years. The rain from Cyclone Bobby and subsequent stream flow was a unique opportunity to create some boating ‘firsts’. Some history-making boating in the desert.

- Cyclone Bobby

- Kalgoorlie cut off.

- Roadwork anger.

- Stranded truckies.

- Traffic flows again.

Lake Boonderoo formed for only the second time in over 200 years. The growth rings from trees felled in 1975 revealed that this year was the first time the Lake had formed in modern times. The lake is south of Kitchener Siding on the Trans Australia Railway, 230 kilometres east of Kalgoorlie.

I planned to mount an expedition commencing from the north-west extremity of Lake Raeside (the longest lake in Australia) near Leonora and navigate its 300 kilometre length south-east to where it overflows into Ponton Creek. This ephemeral creek created a continuous link through to Lake Boonderoo and would be followed all the way to that newly formed expanse of water. By early July I had sufficient information to announce that “the expedition is on”. Planned dates were Friday 8 to Monday 11 September 1995.

Over the weekend of 22-23 July, Tony Overstone, Brian (Justa) Sawyer and I made a survey trip to Coolgardie via Hyden and McDermid Rock to ascertain if The Bus would be able to negotiate the track along which I planned to return from Coolgardie, believing it would be a more interesting trip than the run down the bitumen of the Great Eastern Highway. It was some years since I had been along the track and I knew that it could be impassable after even light rain – a distinct possibility around the planned date of the expedition. During the recce we marked the more hazardous sections of the track with flagging tape. The Bus would get through.

For many weeks prior to the expedition we discussed making a recce of the area in a light plane (Rob Birch as pilot). The main aim was to establish the extent of the water flowing from Lake Raeside. If the expedition was to start from Lake Raeside it was vital that the water was continuous from that point through Ponton Creek to Lake Boonderoo. We eventually decided that the cost of $800 was too much. I subsequently got the information I needed much cheaper by phone calls to the Cundeelee Aboriginal Community and Boonderoo/Kanandah station owner Russell Swan, as well as talks with geologists and sandalwood cutters operating in the area.

- Location of Lake Boonderoo.

Phil Hargrave advised that he and a mate would drive from Adelaide to meet up with us at Kalgoorlie. As a result it was decided to use his vehicle as the Refuelling Vehicle. Ultimately, Phil drove through to Perth a few days early and the expedition was a two-vehicle convoy from the start.

In early August it was decided that the rear springs of The Bus needed resetting. This was a major job that occupied many of the Team over many hours on five separate occasions. Finally everything was ready.

OUR SUPPORTERS

Major expeditions like this don’t happen without a lot of sponsorship and in-kind support. Apart from the members of the expedition who spent many hours preparing boats, motors, vehicles and equipment we were fortunate enough to have assistance from numerous sources.

DEPARTURE THURSDAY NIGHT

Tony Overstone, David Whitney, Phil Hargrave and I each had the day free to concentrate on ‘last minute’ preparations. Phil was engaged in shopping, Tony and David were occupied making a mount for the trailer spare wheel and I was busy worrying.

As others arrived during the late afternoon the packing was completed ahead of schedule. After failed attempts to get away on time on three previous expeditions this one was to prove different. A fair size crowd witnessed the departure from Innaloo.

- Group photo before departure.

The Bus was running well and pulled up Greenmount Hill with comparative ease. After grabbing a bite to eat at Northam it was a steady run through to Merredin.

Problems

Short of Southern Cross the drivers of The Bus reported problems with lack of power and surging. It finally cut out near Southern Cross 25 minutes after midnight. Scott and I bled the engine and we got underway again. Soon after the engine cut out again.

After a more detailed assessment we realised that is was more serious problem than was first believed and one that would not be resolved by just bleeding the fuel system.

The crew in the Landcruiser had pulled ahead but realised that The Bus was not following so they turned around. Cliff joined Scott, Greg and I working on the problem with The Bus. We used the Landcuiser to tow The Bus further off the highway and on to a level patch of ground.

Heads were buried in engine bay, then whole bodies. The generator provided light. The diagnosis was a faulty fuel pump.

- Getting involved.

- Kim conducts.

- Cliff repaired the fuel pump.

Phil set up gas burners and brewed coffee for anyone who wanted it. The dancing light of David’s fire silhouetted their coffee-sipping customers, spectating on the action around the front of The Bus, the steam wafting from their cups. Brrrr, it was cold! White-overalled men moving in and out of the cold fluorescent light imparted a surreal aspect to the roadside scene.

- David lit a fire.

Harsh vehicle lights forced their way through the blanketing envelope of fog. The trucks they were attached to roared past, buffeting The Bus and the crew. None slowed.

Under the bonnet things were getting serious. The fuel pump was removed. The aisle table from inside The Bus was moved out to do duty as a work bench on which the fuel pump was stripped and repaired. After it was replaced the engine would still not start. More investigation. Time was getting away from us. We diagnosed that a blocked fuel line was preventing the engine from starting. That was also fixed.

Underway Again

By 4.45 a.m. all problems were rectified.

This experience convinced me of the need for a compressed air system – which we installed on the return to Perth.

COOLGARDIE DAWN

The schedule was shot. Dawn had broken and were a long way short of Coolgardie – and we were meant to be at Zanthus! Stomachs were rumbling.

“Stop at the next Parking Bay for breakfast.”

Great idea but the next Parking Bay was a long way to the east – about five kilometres short of Coolgardie. It was to be the first use of the new cooking equipment.

While Phil and Kim were cooking bacon, eggs and toast (muesli available for those who wanted it), Tony, Greg and Cliff checked tyres, oil, hitches and the generator. Mike and Scott checked the load on the roof rack. John and Adrian helped the cooks. David was busy taking head and shoulder photographs of most of the crew. Our guests from the fourth estate were impressed.

- Breakfast

Through Boulder

At Kalgoorlie we took the bypass to Boulder with Greg driving. It was his first drive of The Bus and the roundabouts were proving difficult for him.

At 3.9 metres The Bus was too high to fit under the railway bridge out of Boulder. After a few turns around the tailings dumps and settling ponds we found our way out to the access road along the Trans Australia Railway.

I phoned Mrs Swan of Boonderoo Station to advise our imminent arrival and explain our delay.

Along the Trans Line

David was trying to ascertain our position by locating features (dead reckoning). Difficult to do in a landscape largely devoid of features.

Five kilometres after the Golden Ridge siding we crossed first of many grids . This one marked the boundary of the Mt Monger Station.

The vast expanse of country from Kalgoorlie out towards Karonie, through which were now travelling, is known as the Hampton Plains, discovered by explorer surveyor C.C. Hunt while he was looking for pastoral country.

Cowarna Station came and went. Next was Karonie, characterised by salmon gum and mallee. Wildflowers carpeted the country. This part of the world is never truly green, however, after one of the best-ever seasons the trees, bushes and groundcover all looked robust and healthy. For kilometre after kilometre the wildflowers were a profusion of colour; first seas of white, then blue, then yellow and then red disappearing into scrub as far as the eye could see.

- It was a hazardous move to let Tony behind the wheel but everyone else was too tired to drive. Success for Tony was having The Bus airborne over the washaways.

Probably the most exciting part of what was an uneventful trip out to Zanthus was the washaways – sometimes deep, sometimes non-existent. Whoever signposted these depressions certainly was no judge of distance. The ‘Caution Washaway 200 metres’ warning signs were sometimes followed by the hazard within 50 metres. Tony had The Bus airborne on more than one occasion, a fact that made him, not inexplicably, proud of his driving prowess.

At Zanthus the track detoured to the north of the railway. Tony steered The Bus onto the diversion. Adrian and Mike in the Landcruiser continued on along the access road to see what had caused the the need for a detour. It was this section of railway that had been washed out in March after Cyclone Bobby’s rains.

Bogged at Zanthus

The radio blared. “Four wheel drive to bus. Four wheel drive to bus. We’re bogged. We need help.” Tony backed The Bus (with trailer attached) from the diversion road to the original track.

At the intersection we met another traveller. He was geographically embarrassed. David and I gave him a bit of assistance with the maps and showed him how he had arrived at Zanthus instead of Rawlinna, after leaving Balladonia the previous day.

- Navigation 101.

- Explaining to a fellow traveller how he ended up at Zanthus rather than Rawlinna.

- Product placement by Greg.

The old (antique) bicycle on the back of his van drew some attention. After we took photographs of his rig it was off to rescue the hapless 4WD and its crew. In attempting to turn the Landcruiser around the rear wheels had sunk to the axle in the soft mud at edge of the track. Although the front wheels were free they couldn’t get sufficient traction to extricate the vehicle. Half a dozen strong bodies pushing from the rear solved the problem.

- Freeing the Landcruiser.

The next problem was to get The Bus to the diversion turnoff, a kilometre back to the west. There was insufficient room to turn around, complicated by the still-attached trailer. To attempt to turn around meant that it would have suffered the same fate as the Landcruiser – and it would have taken a lot more than half a dozen strong bodies to push it out. We removed the trailer and attached it to the 4WD. Tony then reversed The Bus the kilometre or so to the intersection.

Ponton Creek

Sixteen kilometres after Zanthus the shallow waters of Ponton Creek blocked the road. For those who had seen it before this was an amazing sight. For those who hadn’t seen it before it was an amazing sight. This creek is normally dry and merely a depression in the road. This was our planned overnight stop.

- On the road to Ponton Creek.

The warm afternoon tempted some to wade into the water for a dip. It was cold – and very salty.

- What’s this doing here?

- Selecting our campsite.

It was the middle of the afternoon before the boats were unloaded and rigged ready for a run. The process took a lot longer than expected. Perhaps everyone was ‘bus lagged’.

- Unloading the boats.

Into It

My briefing was short; the time taken for the requisite photo wasn’t.

It was time to tackle the Creek. Paddles were packed in the boats and, as events unfolded, they were needed. Ponton Pool is formed by the road damming the Creek and backing up the waters to where the railway bridge crosses the watercourse. The first 100 metres in the Pool gave a false hope as to conditions farther up the Creek.

- This combination of power dinghies and a full Ponton Creek with a train in the background is a sight unlikely to ever be seen again.

- Another group photo.

I decided that boats were to travel upriver for as far as they could but no longer than one hour and then travel downstream as far as they could but no longer than 1.5 hours. Wishful thinking. They returned after less than 15 minutes. After regrouping they took off downstream with instructions to proceed no longer than one and a half hours. Again, wishful thinking. Just like upstream, downstream of the Trans access road, Ponton Creek was shallow. The channel crossed from side to side and the boats were soon spread out. They had trouble keeping on the plane.

- Kim wanted the boat crews to travel downstream for no longer than 1.5 hours.

- The water didn’t last.

- Actually getting away as a group was no easy task.

Mike and David were in the lead boat when they determined that the Creek was of insufficient depth to provide a passage to Lake Boonderoo. It was a hard slog to return to the Trans access road. Their boat wouldn’t get on the plane with both of them aboard. David insisted that Mike drive back alone while he walked along the bank.

For an activity that is supposedly water based, power dinghy expeditions have, over the years, included a lot of walking.

- Heading down Ponton Creek.

Skurfing Ponton

After the boaters returned from their forays upstream and downstream there was still nearly half an afternoon’s boating to be had. Phil brought out his Malibu surfboard, a rope was found, a handle was fashioned from a conveniently shaped length of salmon gum, and it was time to skurf Ponton Pool.

An appreciative audience sat in the shade of the camp watching the action. Greg’s lightweight boat powered by only an 8 h.p. motor had no trouble getting Phil up on the board. Kim Thorson made it look easy and Bocky also tried his hand. Phil’s version:

“Those guys driving the train must have wondered what in the hell they had come upon. Bit like a scene from Apocalypse Now except most of the time we were our own worst enemy.”

After the skurfers had their fill the boats were loaded onto the roof rack to ensure that we got away on time tomorrow.

- Local resident.

Camp Ponton

As the sun dropped to the horizon so too the temperature dropped. By nightfall it was quite cool.

Past experience had the ‘old hands’ waiting expectantly for Phil and Kim’s culinary masterpiece. The plastic plates detracted not at all from the magic meal. For the ‘first timers’ the chefs’ reputations that had preceded them was vindicated.

Kim Thorson’s version of preparing the first evening meal:

“The persons who packed the food away weren’t the persons cooking or finding the food and the cooks couldn’t find a thing and spent more time looking than cooking. Having an assistant dish dog and frustrated cook in Mr Adrian Bock was a godsend!! He peeled, scraped, grated, stirred, boiled, and cooked. But most important of all he got bourbons and Cokes for the cooks. He was only one who did! And his efforts did not go unnoticed by Phil and myself.”

- Phil cooking for the Team.

TO LAKE BOONDEROO

After greeting the dawn of a new day, breakfasting well and packing the camp it was time to cross Ponton Creek and head for Lake Boonderoo.

- Scott and Cliff at the campfire in the morning.

- Cliff is trying to find Scott.

- Crossing Ponton Creek.

It is about 60 kilometres from the Creek to the Boonderoo Station boundary – 60 kilometres of country devoid of landmarks that would assist navigation. Like yesterday, David was in The Bus trying to determine progress by reference to the maps. The lack of landmarks and no speedometer/odometer on The Bus to determine an average rate of travel or measure distance made navigation difficult (must get that fixed!). Occasional slight direction changes in the road and patches of different vegetation were the main landmarks. Rail sidings were good for positive location fixes but were difficult to spot and generally were only a small signpost on the railway 100-200 metres away.

- 800 kilometres from Perth.

Telecommunication towers were newer than the maps and confused the issue as the signage pointing to them was similar to signage as shown on the map.

At Kitchener, David and I transferred to the 4WD. After an important briefing from Phil on how to drive the compact disc player we took off to scout ahead for the turnoff to the Lake. A large wedgetail eagle eating a ‘roo carcass on the side of the road barely moved as we sped past.

- Crew change. David and Kim moved into the Landcruiser.

The directions I got from Russell Swan of Boonderoo Station were accurate and we located the turnoff without difficulty. We waited for The Bus to arrive and shot off to find the track to the Lake. Again, the turnoffs were easily located. The first sighting of water was not of the Lake proper but merely a backwater or arm. There were soaring wedgies, many ducks, pelicans, coots, teals and quite a few black swans. Tony, driving The Bus, located the turnoff and headed for the Lake, a kilometre away over a small hill.

Into It Again

The ground was firm and Tony drove The Bus to within 30 metres of the water.

Boats were unloaded, motors were fitted, gear was stowed, water bottles were filled, photographs were taken. It all seemed to take so long.

- Arrival at the water’s edge.

John ‘Old Man River’ Haynes posed for press photos at the edge of the Lake and henceforth is known as John ‘Lakeside Retirement Village’ Haynes.

While preparations were underway David was poring over maps to determine the location of this Start Point in relation to the inflow of Ponton Creek. It was difficult to know precisely where this Start Point was so it was decided to simply head around the Lake anti-clockwise and check out any channels the may be the mouth of Ponton Creek.

- Kim and David discussing strategy on how to find Ponton Creek.

Lake Boonderoo

Nine hundred kilometres from Perth, Lake Boonderoo was named only in 1977. It had not been named earlier because it was formed only when Ponton Creek flooded after a cyclone in 1975. The Lake filled to a depth of approximately 20 metres and covered an area of 15 square kilometres. It still contained a considerable quantity of water when named in 1977. The water remained for a further eight years

The claypan that existed before the Lake filled was named Yandallah in 1919 by a Mines Department geologist, H.W.B.. Talbot. However, instead of using this name for the Lake in 1977 it was named after the Station on which it is located. The name ‘Boonderoo’ means ‘stony country’ in the Tjeraridja dialect.

When the Lake flooded in 1975 trees within its periphery died after having been inundated. Scientific analysis of these trees revealed that they were in excess of 200 years of age, indicating that the Lake had not flooded for a least that period. This was the reason for its lack of a name.

Lake Boonderoo’s water starts its journey more than 600 kilometres to the north-west, at the beginning of Lake Raeside, east of Leonora.

The sheer extent of the Lake was difficult to comprehend. At times, when in the centre of its expanse, land could not be seen. Full grown trees were flooded by its waters and could be clearly seen from the surface.

Based on experience from the previous flooding it is believed that it will not dry up until about 2005. Though being fed by the salt water of Ponton Creek, the lake water is quite fresh.

Lake Boonderoo is on the western edge of the Nullarbor Plain.

Boating on Boonderoo

- The start of the Boonderoo Blitz – and a little bit of boating history.

- John and Scott in the SS Shower Rose.

David was navigating, searching for the mouth of Ponton Creek:

“We drove through trees along the shoreline and investigated many likely looking channels on the western edge of the Lake. Once we entered a large body of water that I determined to be a continuation of the Lake not shown to be connected to the main Lake according to our maps. After a few hours of searching we saw a patch of high ground on the water’s edge where we could have lunch on dry land.

During our lunch here I took the map and climbed to the highest point of the rise (not big enough to be called a hill) and had a good look around. At this point I was fairly sure I knew where we were and also that we had somehow missed the outflow of Ponton Creek just before stopping for lunch.

- Soon after the start.

After lunch we doubled back for a while looking for the channel. It started to look as if we were going to backtrack over water already explored and everyone was getting tired of looking for the Creek so we collectively decided to circumnavigate the Lake instead.

Once in the main body of the Lake and travelling fairly fast it became easier to relate features on the shoreline to the map and I became certain of our current location.

On the eastern edge of the Lake, as we headed north, we noticed a fairly high rise on the shoreline that was a different colour to the surrounding countryside so all the crew pulled in to shore.”

- Somewhere on Boonderoo.

Scott was in the SS Shower Rose with John.

“We decided to climb the hill to get our bearings and attempt some radio contact. When I jumped out of the SS Shower Rose I started to sink while pulling the Rose onto the bank. By the time the boat was ashore I was buried up to my thigh in mud.”

- Somewhere else on Lake Boonderoo.

David walked to the top of the hill:

“It was barely big enough to rate being called a hill. The soil here was soft powdery white, almost like talcum powder. Scott had brought the radio to the ‘summit’ and we were able to call Kim at the base camp and advise that all was ok and provide him with a map reference of our location.

We continued north again along the eastern edge of the Lake where the water was starting to become very rough as the breeze had a chance to whip up the chop as it crossed the widest point of the lake. The north-eastern corner of the Lake was good fun for boating as the water was a little more sheltered and we were all able to zip in and out among the numerous trees along the shoreline.

- A backwater.

- Same backwater.

Along the northern edge the trees were still good fun and everyone thought it would be an excellent site for a boat race through the natural obstacle course.

As we turned north onto a branch of the Lake the countryside suddenly looked familiar and we spotted The Bus at the now established campsite on the shoreline. I had not expected to be back at our start point so soon but I then realised that I had been out by about a kilometre in my original estimate of our camp location.

It was Phil’s first time in a plastic boat. All his previous power dinghy racing had been in a ducky. He was crew for Greg:

“Greg and I had a ball. I now realise why Greg kept saying’ “Watch the nose”. The bloody thing submarined on us once and luckily we got away with it. Greg’s a ‘hoon’. He loves carving a new path and more times than not through the trees rather than around them. Ask him how he feels about spiders though and you’ll get another answer.”

- Captain Chaos

- Pit stop.

- Looking for this creek sure is exhausting work.

- Are we having fun yet?

- Lose the water and you walk.

- Typical Nullarbor country.

- Now we’re having fun.

- Serious fun.

- The SS Shower Rose.

- Greg and Phil.

- The breeze roughed up the water.

- Heading ‘home’ on Saturday afternoon.

Camp Boonderoo

Meanwhile Kim Thorson, Tony Overstone and I selected a fine site for the camp, among the saltbush and bluebush on a gentle slope overlooking the Lake.

After the exertions of setting up camp with its magnificent view overlooking the Lake the three support crew decided it was time for an afternoon nap.

A restful afternoon it was not to be. The peace was disturbed by a profusion of annoying, clinging flies and a similar profusion of calls on the radio from Scott.

“Nave Boat to Bus, Nav Boat to Bus. We are are at grid reference 295 520. What’s the reception like?”

“Thanks guys, wonderful to know it works, wonderful to know where you are. Now can I resume my rest?”

One might get the impression that the support crew were not playing the game.

Approaching camp, the boat crews decided to see who could get their boat closest to The Bus – 400 metres up the gentle slope.

“Yeah, right, Tim.”

Mike landed 80 metres away from where the Landcruiser was parked near the water’s edge and so had to drag his boat back into the water and try again closer to where all the other boats had been beached with varying success.

- No need to get the feet wet.

Scott’s version of events:

“When the beach landings started everyone was standing around and laughing at the efforts. Then Cliff headed off for supposedly the beach landing to end all beach landings. I could see him winding up on the horizon. There was only one gap left among all the other boats. About 30 metres up the path was a rather big log. I started to move it and a few guys commented that he wouldn’t even get close. When he went past where the log had been he still had the motor hard into the mud looking for extra drive with sticks and crap flying everywhere.”

- Retired racers don’t attract a penalty for beach landings.

- Greg ready to go.

- The downside of great beachlandings.

- Waiting for Cliff’s huge beachlanding.

It was late afternoon. The boating was finished and it was time to relax. David finished off the firepit I had started digging ready for a mammoth fire.

The setting sun provided moments of magic as it slipped below the horizon.

- Mike and Adrian at ‘Camp Boonderoo’.

A few cold drinks, a comfortable seat in front of the flickering flames, a few tall tales and life was pretty fine.

Kim Thorson and Phil, ably assisted by Adrian, performed minor miracles in the kitchen or, as they termed it, the Desert Diner,

Even though the campsite was on the edge of the Nullarbor Plain, there was enough fallen timber for Tony to run amok with the chainsaw and cut sufficient wood to make, in David’s words, “a respectable sized camp fire”.

- I told you not to smoke while refuelling.

- Mike’s moustache is alight.

It was a cool night.

Phil decided to remove some extraneous items from inside his Landcruiser so he had enough room to sleep in it. Scott gave him a hand:

“Phil and I grabbed some stuff out of his 4WD and the Phil picked up the fire extinguisher. Somehow the safety pin had been removed so when Phil picked it up it went off with a bang (as they tend to do) half filling his 4WD with powder. Phil was left in a powder cloud wondering what the hell happened. He was peering through the cloud seeing me laughing my head off without any powder on me. I heard the seal break and knew exactly what had happened and, knowing the consequences, got out of the way.”

NULLARBOR MIST

The early morning mist was typical of the Nullarbor. It topped out about 1.5 metres from the ground in a very straight horizontal line, giving a surreal atmosphere to the dawn. Heavy dews are frequent on the Nullarbor and are almost as serviceable as good rains to saltbush, bluebush and similar plants. It was a cool morning, indicative of just how far inland we were.

- Just after sunrise.

- “Cold, Scott?”

- Let out for the day.

Locating the Mouth of the Ponton Creek.

Spare motors, spare parts, lunches, emergency rations and other unnecessary weight were dispensed with for the morning’s run on the Lake to attempt to find the mouth of Ponton Creek.

Five boats were on the water, two with three crew each. Cliff volunteered to stay behind at camp. The extra personnel meant the variables of engine power, boat carrying capacity and crew weight had to be juggled to get optimum performance. Eventually I ended up driving John’s boat with David navigating. Adrian and Scott teamed up, and Tony and John used Cliff’s inflatable. Greg’s oversized surfboard carried both Chefs. Mike’s inflatable was the Press Boat.

- So long since he’s been in a boat he’s forgotten how to do up the chinstrap.

- Leaving camp.

- Early morning on a big lake.

- Dinghies in line.

The original inaccurate estimation of the location of the Start Point contributed to not being able to find the mouth of the Ponton Creek the previous day but since David now had some landmarks he was confident of knowing where it was:

“We were heading toward the high point where we had lunch yesterday and I was planning to head west shortly before we reached the shore. Along the way we set up a few photograph opportunities for Tom while zipping in and out through the trees.”

- Greg chauffeured the two Chefs.

- Kim and David trying to find Ponton Creek.

- Bocky and Scott manoeure the ducky through the trees.

- Greg, Kim and Phil in the trees.

“Once we reached the bank I was aiming for we headed west but all the time keeping the left or southern bank of the Lake in sight. We were passing through what seemed to be a very wide channel with trees all the way round us and we had to maintain discipline to keep each other in sight.”

- Inundated 20 metre tree, still with foliage.

- Greg, Kim and Phil.

- Bocky and Scott.

“The plan was for each boat crew to ensure that they could see the next boat behind at all times and stop and even retreat if necessary. We were careful not to venture into any other promising channels and fortunately drove pretty well straight into the mouth of Ponton Creek.”

- The mouth of Ponton Creek.

“We could tell that we were close to the Ponton Creek outflow when the water started to taste salty. The vegetation on the banks of the Creek had muddy water marks nearly two metres above the current water level. Judging by the appearance of the edges of the Lake elsewhere, the water in the main body of the Lake was at its peak level at the moment.

The higher water marks even 50 metres up the narrow portion of the Creek indicated that during the peak flow the water must have dropped two metres in the final dash from Creek to Lake. This must have been an awesome sight as the only other place I have seen water banked up this high without any real physical barrier to retain it is an ocean surf break.

All the boats went a little way up the creek until we reached shallow water. Kim and I were having trouble keeping the boat afloat every time we slowed too much for the water to drain. Two boats carried on and went about five kilometres up the Creek and on their return we sped directly back to camp.”

- Kim and John chat at the mouth of the Ponton Creek.

After lunch we packed the camp and loaded some boats.

Tom went skurfing behind Greg’s boat. Cliff then took Greg’s boat out by himself to assess the performance of the Suzuki motor. He was impressed and gave it a good workout. A considerable time later he was still throwing the boat around, stoping, starting, turning and generally enjoying himself.

“Hey, give me my boat back!”

Cliff later bought a Suzuki motor.

- On the Trans Access Road heading to Coolgardie.

We left Boonderoo mid afternoon with Tony driving.

- Greg has found something.

- The country was carpeted in wildflowers.

- On the Trans Access Road.

Shortly after David took over driving near Zanthus we had a flat, right rear. A large chunk of rubber had come away from the tyre.

- Fixing a flat tyre near Zanthus.

- Same flat.

We continued our push west into a setting sun.

After refuelling the expedition headed south from Coolgardie towards the planned overnight stop at Gnarlbine Rock. We forgot to replenish water supply at Coolgardie. This had ramifications when attempting to wash dishes that night and the next morning.

The Gnarlbine Rock campsite (chosen at night but with prior knowledge) capped off a series of campsite selection that was particularly pleasing. Considerable effort and forethought was put into the selection of the campsite at each of the overnight stops. It was never a case of “this will do”. Particular attention was paid to ensuring that the site selected was the best available. A good site for the overnight stop adds to overall enjoyment of the trip. After all, the food was fine, the experience was exhilarating, the weather was wonderful, the company was convivial; why not make the siting of our temporary home as good as one could get. From the first night on the banks of the Ponton Creek to the gentle slope overlooking Lake Boonderoo and finally this campsite with the ancient Rock as a backdrop, each campsite was a masterpiece of perfect aspect, great view and comfortable surroundings.

HEADING WEST

Warned that this would be a ‘big’ day in terms of things to do and distance to travel, everyone was up earlier than usual and the preliminaries to the day were completed earlier than usual.

- Breakfast in the sun.

- Kim, Mike and Tom finish the dish washing.

- About to leave Gnarlbine Rock ion Monday morning.

Once both vehicles were packed it was time to look around the area – one so important in the discovery of the eastern goldfields.

We explored the rock and the area on the opposite side of the road, and then inspected a monument and plaque erected at the base of the rock by the Eastern Goldfields Historical Society.

- Draw at thirty paces.

The variation in vegetation is very noticeably linked to the variation in soil type. The bush was mostly scrub heath and broombush thicket interspersed with salmon gums. The lack of large gimlet gums and other large trees south of Coolgardie can be found in the history of the Eastern Goldfield’s early mining days.

Large uninhabited area south of Coolgardie

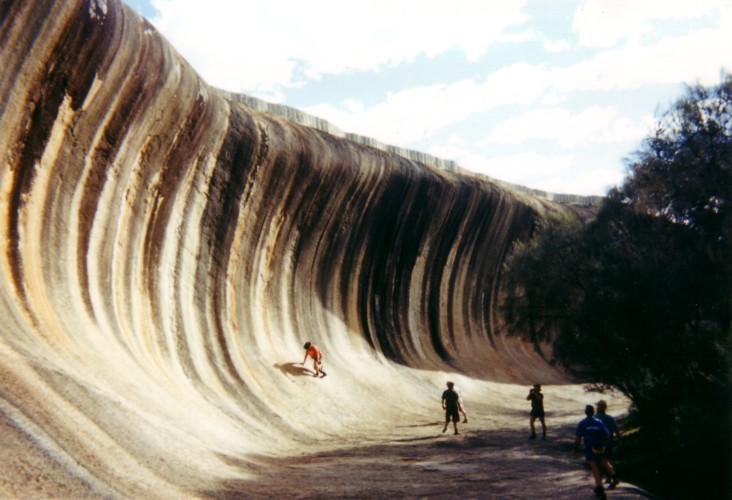

Victoria Rock was named by John Holland in 1893 when making his time-saving track to the Goldfields. Trees and other vegetation are present right up to the edge of the Rock, as it is with other granite outcrops such as Wave Rock, King Rock, The Humps, McDermid Rocks and Gnarlbine Rock.

- Atop Victoria Rock.

- Descending the rock.

We continued south on Victoria Rock Road and then turned right onto the Hyden Norseman Road, a great shortcut between Perth and Norseman.

A couple of kilometres along this road is the access track to McDermid Rock.

- First look at the waves of McDermid Rock.

- Look carefully and you will see a person in the centre of the photo. It is a big rock.

At McDermid Rock we lugged the boats to a point above the first “wave” and had bit of fun surfing the ‘McDermid Break’.

- Talk about a dry argument.

- Adrian and Scott surf the McDermid Break.

- Hamateurs.

Phil departed the expedition at McDermid Rock. He turned left, The Bus crew turned right.

The road from Forrestania to the Vermin Proof Fence was rough. The corrugations threatened to shake The Bus apart. At one stage the vibration was so bad there was nothing else to do but laugh. Everything was jiggling, shaking, vibrating and making a racket. The din was incredible. The road improved after the turn off to a mine to the south.

- A huge fire in January 1993 burnt out 400,000 hectares. The fire front stretched 110 kilometres and burnt for four months. The bush is only just starting to regenerate.

Burnt bush was a sorry sight. The bush had yet to regenerate. Many kilometres later the seas of green paddocks were a marked contrast to the blackened expanses seen for the last thirty kilometres.

Into Hyden. We looked around Wave Rock, the Breakers and Hippos Yawn before heading to Perth.

- Scott, Adrian and Nick at Hippos Yawn.

- At Wave Rock. Someone always try to climb the face. On ya, Doctor.

- Playing tourists at Wave Rock.

Near Corrigin Kim Thorson averted a disaster during his driving stint. A tour coach full of pensioners moved out to pass The Bus. The driver must have been blind or on drugs because he failed to see the oncoming light truck. Kim swung The Bus out to block the path of the tour coach and forced him back onto the left side of the road. The oncoming vehicle passed safely, the tour coach overtook us safely and it was back to the humdrum of the trip home.

Early October and there’s a drama about the use of Sunday Times’ photographs. Contrary to arrangements made prior to departure, the photographs are available only in black and white (for heaven’s sake, it’s 1995 not 1965) and at the standard price the public is asked to pay. It seems that we should have put everything in writing – there is no such thing as a “gentleman’s agreement”. In the world of newspapers, like politics, perception is reality. The perception that the negatives of all shots taken would be made available was made very real by the words used before and during the expedition. No “maybes”, no “see what I can do” – plenty of “no problems”, plenty of “they’ll only go in the bin, anyway”. However, on arrival back in Perth the situation changed and we were on the outer.

The most annoying aspect of the matter is that because it was believed that the Sunday Times’ photographs would be available, participants who would otherwise take photographs (Tony Overstone, Phil Hargrave, Kim Epton) did not take their cameras, or did not use them.

If you’re in the newspaper industry, the need to keep one’s word is as real as the series of boating firsts on Lake Boonderoo that the Sunday Times’ Magazine article covered.

After appeals were made to the Chief Executive of the Sunday Times, Bill Reppard, at the end of October, the photographs were made available. But why was the drama created in the first place? All it did was create a poor relationship when there was no need.

© Kim Epton 1995-2024

6744 words.

Text and Layout

Kim Epton

Additional contributions by:

David Whitney

Kim Thorson

Phil Hargrave

Scott Overstone

Adrian Bock

422 photographs.

Tom Rovis Hermann

David Whitney

Kim Thorson

Greg Barndon

Cliff Hills

Feel free to use any part of this document but please do the right thing and give attribution to adventures.net.au. It will enhance the SEO of your website/blog and Adventures.

See Terms of Use.