Jimbine Rockhole is a rarely-visited, aboriginal water source in the Helena and Aurora Range. It is not listed in official records.

The following text and photographs have been extracted from Lesley Brooker’s excellent book, Explorers Routes Revisited – Clarkson Expedition 1864:

“According to Harper, the party crossed the range about 8 miles north-west of Mount Kennedy, and the continued on for another 5 or 6 miles. Therefore, I calculated that Jimbine must have been somewhere in the vicinity of 30o17’S, 119o35’E. Consequently Michael and I circumnavigated the Helena and Aurora Ranges to this approximate location on the northern side. Finding nothing near the track we began a search on foot. About 100 m east of the track, on scalling a low rise, we were astonished to find a clearing in the next valley that contained a natural well in the conglomerate sandstone, exactly as Harper had described it.

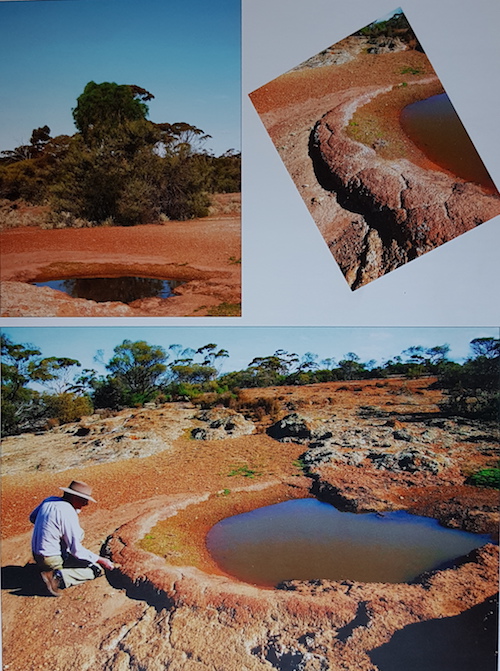

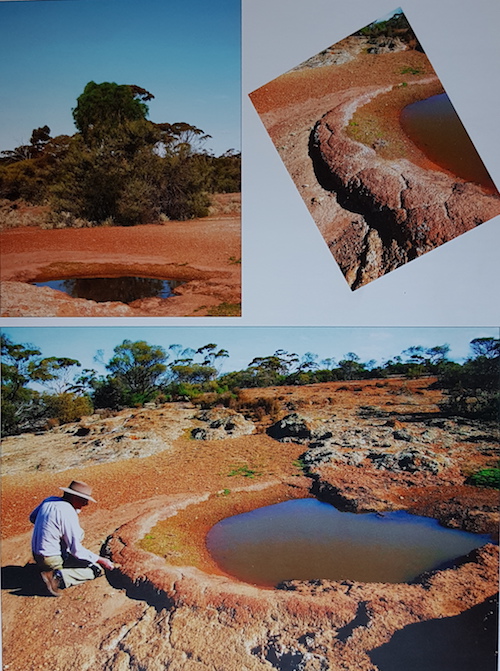

Jimbine is on an open gravelly hillside with outcropping laterite and fringed with open woodland. The rockhole itself measured from 2 to 3 metres in diameter and held water to the depth of at least 1 metre. It was fed by a small eroding drainage line from a rise to the south. The lower perimeter of the well was composed of reddish sandstone, with a relatively smooth, rounded rim, which was so regular that one could almost believe that it had been worked to give it that finish. Surrounding the well for at least 300 metres on all sides, the ground was covered with broken, worked flints.

There was no sign of European interference with the site and nobody had visited it recently. From the hillside beside the rockhole, the peak of Mount Kennedy (Bungalbin) could be seen to the east of south, 12 kilometres away.

Clarkson, Harper and Lukin would camp at Jimbine for the next three nights, while making daily forays to the surrounding areas and so I imagine that the rockhole may have deeper in their day, kept free of debris and sand by the local Balcup Aborigines.”

-

-

Jimbine Rockhole in 2008. Taken from page 60 of Lesley Brooker’s book.

-

-

Jimbine Rockhole in 2008.

The name Jimbine is not in Geonoma, Landgate’s database of geographic names. Most of the names used by Clarkson, Harper and Dempster were either changed or ignored by the authorities at the time.

Reference:

Brooker, Lesley, Explorers Routes Revisited – Clarkson Expedition 1864, Hesperian Press, Carlisle, WA, 2012, p60-61.

© Kim Epton 2017-2024

428 words, two images.

Feel free to use any part of this document but please do the right thing and give attribution to adventures.net.au. It will enhance the SEO of your website/blog and Adventures.

See Terms of Use.