THE NEGEV DESERT

The Negev Desert covers more than half of Israel, in excess of 13,000 km2, but has only 8% of its population. It forms an inverted triangle shape contiguous with the Sinai Desert on the west, and the Arava valley to the east.

The Negev is a rocky desert. It is a melange of brown, rocky, dusty mountains interrupted by wadis (dry riverbeds that bloom briefly after rain) and deep craters, an area that has an average annual rainfall of less than 200 millimetres.

- The Negev Desert

It is divided into several regions, starting with the Be’er Sheva-Arad rift in the north, to the mountain ridge in the centre and the Arava and Eilat in the south.

The Negev Desert includes three enormous, craterlike makhteshim (box canyons), that are unique to the region; Makhtesh Ramon, Makhtesh Gadol, and Makhtesh Katan.

The landscape where the trip took place is mostly Eocene (50 million years ago) limestone, consisting of some brown-black layers of low-grade flint. The erosion of the limestone is slowed by the flint it covers.

The wadis and nakhals are excellent for motorcycling and four wheel driving – and some people even use Shanks’s pony.

Various peoples have lived in the Negev since the dawn of history: nomads, Canaanites, Philistines, Edomites, Byzantines, Nabateans, Ottomans and of course Israelis. Their economy was based mainly on sheep herding and agriculture, and later also on trade.

The modern Israeli settlement of the Negev began about 100 years ago, when a few communities were built.

These were joined by another 11 settlements whose founding members built the first homes in a single night.

After the establishment of Israel, the new country’s first prime minister, David Ben Gurion, promoted the settlement of the Negev Desert and after he moved to live in Sde Boker a few more settlements were built.

PREPARATIONS

The trip to the Negev Desert by motorcycle and 4WD was planned as a birthday bash for Ehud on his return to Israel to see his family and friends.

Work on preparing the five motorcycles, two KTM 400s, one KTM 125, a Husqvarna 250 and a Yamaha WR450, for a gruelling desert trip had been underway since Ehud arrived. All bikes were fitted with new tyres. The Husky was fitted with a new valve spring, requiring removal and replacement of the cylinder head the night before departure.

- Ofer and The Beast.

- Tricked up Prado.

The two main support vehicles were Ofer’s 2008 twin turbo Ford 350 pickup truck (ute) and the Powitzer family shopping trolley, a 2001 Toyota Prado. As Matan arrived in Arad separately in his Prado, there ended up being three support vehicles.

I flew in from Australia via Bangkok late on the 19th and the crew was complete.

DAY ONE – Thursday 20 September 2012

DAY ONE – Thursday 20 September 2012

After a leisurely packing the expedition got underway from Hod Hasharon about 9.30 a.m., heading south on the motorway before turning east on Route 31 towards the departure point, Arad – Israel’s second largest city (by area) and a globally-renowned retreat for asthmatics – about 150 kilometres distant.

- Enosh at the departure point.

- Preparing to depart.

Final preparations were made in the shade of a disused building at Arad.

INTO THE DESERT

A few kilometres after leaving the start point at Arad, Ofer and I (in the Prado) left the bitumen to travel through the Judaean Desert Nature Reserve (Midbar Yehuda ha-Tikhon Reserve) and rendezvous with the bike crew.

Nimrod, Ehud, Ohad, Matan and Ran in the bike crew took a more southerly route through the Nakhal Abul Reserve.

Enosh in the F350 and Kerry in Matan’s Prado headed to a yard in Moshav Ein Yahav, owned by one of Ofer’s Army friends, where they had a leisurely afternoon looking after Jonathon and Sean, and ready to give assistance to the bike crew should it be needed.

- Ancient Judean Desert.

- Barren Judean Desert.

- Barren landscape of the Judean Desert.

- Judean Desert.

THE DEAD SEA

The track through the spectacular Judaean Desert leads to a magnificent 400 metre high vantage point overlooking the Dead Sea.

- Bikes approaching the Dead Sea cliff from the Judean Desert.

- Out of the Judean Desert to the cliff overlooking the Dead Sea.

- Ehud at cliff overlooking the Dead Sea.

- The Dead Sea.

- Above the Dead Sea.

- Cliff overlooking Dead Sea.

- Ohad, Ehud and Nimrod watching Ofer making coffee. Ein Bokek in the background.

- Kim and Ehud.

At 418 metres below sea level the shore of the Dead Sea, shared by Israel, the West Bank and Jordan, is the lowest dry land point on Earth.

Ein Bokek resort on the shore of the Dead Sea (and seen in the photograph above) is one of a number of resorts and spas in both Jordan and Israel that offers access to the reputed therapeutic benefits of this unique place.

Just after 3.00 p.m., Ofer and I headed down the cliff in the Prado to Route 90, the highway that bisects Israel from north to south.

Wadi Bokek is at the bottom of the cliff, just before turning onto the bitumen. It was then only a few kilometres to Wadi Sedom and the supposed site of the notorious biblical town of Sodom (and Gomorrah).

- Overlooking the Dead Sea.

- The Dead Sea.

- Ein Bokek at the Dead Sea.

- Nimrod contemplating.

- Track down the cliff to Ein Bokek.

- Prado on the track down to the Dead Sea.

- Track down cliff to the Dead Sea.

- Track down the cliff to the Dead Sea.

SEDOM

The bike crew headed along the cliff top track, crossed Route 31 and made their way into Wadi Sedom.

Sodom and Gomorrah were cities mentioned in the Book of Genesis and throughout the Hebrew bible, the New Testament as well as the Qur’an.

The name Sodom is derived from modern Hebrew ‘Sedom’. The exact meaning of the name is uncertain. The name Sodom could be a word from an early Semitic language ultimately related to the Arabic sadama, meaning ‘fasten’, ‘fortify’, ‘strengthen’. So much for the name – the city was unable to fortify itself against god’s wrath.

Divine judgment by Yahweh (Jehovah – the god of Israel in the Hebrew bible) was passed upon Sodom and Gomorrah (along with two other neighbouring cities) and they were completely consumed by fire and brimstone. In Christian and Islamic traditions, Sodom and Gomorrah have become synonymous with ‘impenitent sin’, and their destruction with a proverbial manifestation of the Christian and Islamic god’s wrath.

The historical existence of Sodom and Gomorrah is still in dispute by archaeologists, as little archaeological evidence has ever been found in the regions where they were supposedly situated.

Have these archaeologists not seen the signpost pointing to Mt Sedom?!

- Mt Sedom signpost – in English and Hebrew.

- Near Mount Sedom.

- Ehud and Ran.

- Near Mount Sedom.

- Nimrod, Ehud, Ohad, Matan, and Ran.

After some revised route planning the bike crew headed to a plateau named Mishor Pratzim just before 4.00 p.m.

- Ofer, Matan and Nimrod discussing the route to camp.

Ofer and I drove to the Monks Cave on the east bank of the Wadi Zin. Although there are thousands of caves in the country, including hundreds in the Sedom area, little is known of the handful of monks’ caves.

- Ofer approaching the cave

- Inside the Monks Cave.

- Cross in Monks Cave.

- A cross in relief on the wall of the cave.

- View from the Monks Cave.

- Prado at the Monks Cave.

The Nahal Zin is 120 kilometres long and is the largest wadi in the Negev. The formation of the wadi is interesting. It was created by ‘reverse erosion’. The great height difference between the Negev Highlands and the Jordan Rift Valley caused the under layers to erode during the rainy season, resulting in the collapse of the harder strata of rock above.

Ofer and I met up with the bike crew in Wadi Zin on the way to Moshav Neot HaKikar and we then travelled together along Route 2499 (a side ride that leads east and ends at the border with Jordan), stopping at a natural swimming hole just before the moshav.

The route then took us through Wadi Amatzia to Ein Katzeva fuel station.

- Wadi Amatzia

- Wadi Amatzia

- The Prado at Wadi Amatzia.

- Wadi Amatzia

- On the Spring Route.

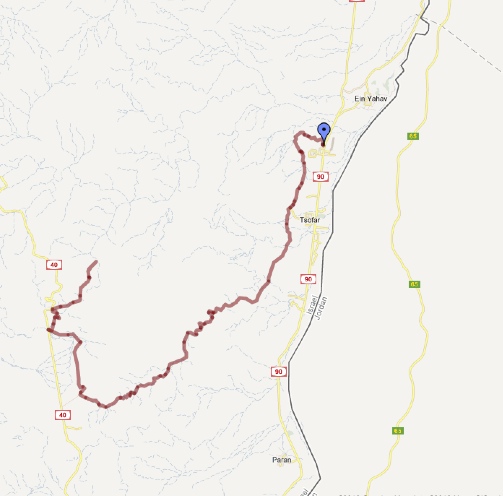

The bike crew took what is known as the ‘spring route’, parallel to but west of the bitumen, to Wadi Nekarot and then headed east down the wadi (towards Route 90), to the night camp.

Meanwhile Ofer and I went to Moshav Ein Yahav, collected Kerry and Enosh and drove across the bitumen to the overnight stop, about 700 metres into Wadi Nekarot.

- Ran

The expedition centred on Ein Yahav, a moshav 100 metres below sea level, and home to about 500 people, many of them ‘guest’ workers from Thailand.

There is an early Bronze Age copper-smelting site near Ein Yahav.

- Day One Route

The overnight camp was under a single acacia tree in a protected position not far from Route 90. Although reasonably well-used, it was acceptably clean and rubbish-free.

- The fleet after Day One.

- At camp.

- Kerry at the first camp.

- Ohad stretching after a strenuous first day.

- Ohad thinks he working on a bike.

- Ran preparing dinner.

DAY TWO – Friday 21 September 2012

DAY TWO – Friday 21 September 2012

There were some early risers but it was 7 30 a.m. before most were awake.

- Weren’t they doing that last night?

Breakfast is the most important meal of the day. Enosh and Ran, with a lot of advice from everyone else, prepared shakshuka, which, I am reliably informed, is a traditional Israeli breakfast dish.

- Ran preparing breakfast.

- Enosh helped.

- Shakshuka ready to cook.

- Shakshuka for breakfast.

In the mood from cooking breakfast, Ran volunteered to be ‘camp dog’ and after cleaning up and packing ’The Beast’ he was to make his way to the pre-arranged lunch spot at Wadi Nekarot.

- Boredom is the precursor to many strange activities.

Nimrod, Ehud, Ohad, Matan and Enosh headed down the bitumen on their motorcycles to refuel at Sapir. They then rode north-west a short distance along the ‘spring route’ before heading to Moa and then generally south along the Arava Valley.

Ofer, Kerry, Jonathon, Sean and I in the Toyota Prado went to the service station at Sapir and there met up with some fellow adventurers also doing a desert trip. They were using road-licensed, Polaris RZRs (commonly known as Razors).

- Razor refuelling.

- Desert ready.

- Ready for a weekend in the Negev Desert.

- One downside is lack of space.

- Great suspension setup.

- Had a proprietary navigation system onboard.

MOA

After refuelling the Prado we headed south again on Route 90 and then about 11.00 a.m. turned into the Arava valley towards Moa.

Moa was an ancient Nabatean caravanserai/ fortress established in the third century BCE on the Incense Route, a network of trade routes extending over two thousand kilometres to facilitate the transport of spices, incenses and other goods from the Yemen and Oman in the Arabian Peninsula to the Mediterranean. The Nabatean merchant caravans arrived at Moa after crossing the Arava Desert.

- Moa hotel ruins

- Moa hotel ruins.

The remains of the square fortress, the khan, agricultural installations, a water storage pool, the aqueduct, and a special olive press are still visible.

From Moa the Nabatean’s main route continued past Metsad Nekharot to Saharonim khan at Makhtesh Ramon. Moa was abandoned in the third century CE, probably because of the outbreak of an epidemic.

What remained is the biggest, most impressive and best preserved archaeological site in the Arava.

Moa and the four Nabatean towns of Haluza, Mamshit, Avdat and Shivta were a vital part of the Incense Route, and collectively were proclaimed a world heritage site in 2005.

WADI OMER

For the interested observer, the stratified cliff faces of the Omer Ridge are a real world display of geology – synclines, anticlines/antiforms and other structures and deformations being clearly visible.

- Wadi Omer

- A desert feature.

- In the Negev Desert.

Ofer drove the Prado up Wadi Omer, looking for the track that would take us up on the ridge to Fort Qatzra where we again sighted the five RZRs, also checking their navigation.

FOSSILS

We eventually located the correct track. Part way along the ridge Ofer slowed the vehicle to a stop and without saying anything began walking back downhill along the track. He signalled for Kerry and me to join him and Kerry drove the Prado down to where he was waiting.

He was standing in a ‘nest’ of fossils.

- Lots of fossils.

- Kerry with a fossil.

- Even more fossils.

- Kerry and Ofer.

FORT QATZRA

At Fort Qatzra (Metsad Katsra) we caught up with the Razors for the third time.

The top of this hill was the site of a Roman Nabatean fort on the Petra to Gaza Incense Route.

- Ruins of Metsad Katsra.

- The commanding view from Metsad Katsra.

INCENSE ROUTE

The Incense and Spice Route was one of the main trade routes of the ancient world that connected the Roman Empire with Asia. It crossed the Arabian and the Negev deserts thorough Petra, the Nabatean capital, and continued to the port of Gaza on the Mediterranean shore.

- Metsad Katsra

- Metsad Katsra

The Spice Route derives its name from the exotic spices like frankincense and myrrh that were traded by the Nabateans. A simple analysis would reveal that the infrastructure and logistics provided by the Nabateans would require more than just spices and incenses to sustain it – and indeed these ‘Desert Masters’ were involved in trading incense, gold, animals, iron, copper, sugar, medicines, ivory, perfumes and fabrics.

- View from Metsad Katsra.

- From Fort Katsra.

- Hercules were a common sight in the Negev.

- From Metsad Katsra.

NABATEANS

The Nabateans built service stations for the caravans: inns and whorehouses, water storage facilities, forts and a complete road system.

The Nabatean settlements were spread out in such a way that they could efficiently maintain the many-branched system of routes crossing the Negev. The towns were spaced about 35 kilometres apart – a day’s travel for a camel.

- The Incense Route

- The Negev Desert

They knew how to lead convoys through the desert to the sea and thus they controlled the Incense and Spice Routes. And control of this crucial trade route between the upland areas of Jordan, the Red Sea, Damascus and southern Arabia was the lifeblood of the Nabatean Empire.

The Nabateans knew how to hoard water in simple but ingenious ways and built hidden underground reservoirs with plastered walls that assured them a secure supply of the life sustaining liquid.

- Nabatean reservoir at Metsad Nekarot.

- Inside the reservoir at Neqarot.

- Reservoir at Metsad Nekarot.

- Neqarot reservoir from the inside

Their prosperity and economic success greatly influenced their culture and lifestyle and so from desert nomads they became permanent residents of urban settlements. They left behind them impressive ruins of their towns, especially those of Petra in Jordan.

The Nabateans flourished from the third century BCE to the third century CE.

RIVER KHADAV

The bike crew left the valley, crossed and re-crossed Route 40 and then rode along the River Khadav north to the lunch rendezvous.

- Now, where are we?

- It’s his fault we’re lost.

- Let’s examine the situation.

- The track petered out and the only way to the Khadav River was cross country.

- Puncture repair under the solitary bit of shade that could be found.

- Hot around River Khadav.

- River Khadav

- River Khadav

In the Prado we rendezvoused with Ran in the F350 at Wadi Nekarot for lunch and a short time later the bike crew arrived – some nearly missing the spot. Lunch was a leisurely affair. It was hot and the sleeping mats Ran had spread around were inviting. It seemed that the crew were going to spend the rest of the afternoon under the shade of the acacia tree until I stirred them up.

- Nimrod and Ehud at Katsra.

After lunch at Metsad Nekarot, the bike crew took a southerly route, cutting from Wadi Nekarot to Katzra ruins and through Wadi Katzra before describing a big loop to head north again, riding on to Sapir Park swimming pool.

MAKHTESH RAMON

After lunch Ofer and I shot off to pass a group of tyro four wheel drivers heading to the makhtesh, not wishing to get stuck behind them on the difficult track into Ramon. We ‘ascended the stairs’ to the makhtesh just before three in the afternoon.

- Inside Maktesh Ramon.

A makhtesh is usually referred to as a crater, but it is not an impact crater from a meteorite – it is actually a valley surrounded by steep walls and drained by a single wadi. At 40 kilometres long and nine kilometres across at its widest point, Makhtesh Ramon is the world’s largest makhtesh.

- Inside Maktesh Ramon.

Mount Ramon, at the south-west corner of the makhtesh, is the highest peak in the Negev at 1037 metres. The name Ramon comes from the Arabic “Ruman” meaning Romans.

Fossils, rock formations and volcanic/magmatic phenomenon in Makhtesh Ramon date back as much as 220 million years, considerably older than much of the Negev.

The Ramon crater began forming when the ocean that covered the desert at the time began to recede north. Makhtesh Ramon is about 500 metres deep and its lowest spot, Ein Saharonim (the Nabatean khan after Moa), contains its only natural water source.

The makhtesim are unique to the Negev. They are the only complete exemplars of their kind in the world.

Ofer and I drove along the Ardon River inside the makhtesh to the much-photographed dyke.

- Dyke inside Ramon Crater.

Dykes in the makhtesh are igneous intrusion from volcanic activity into the sedimentary rock formation. They are also known as magmatic seepage.

The Ardon River dyke track led back to ‘the stairs’ and when Ofer and I arrived mid-afternoon the group of four wheel drivers we had passed on the way in was attempting to climb this difficult section of track. Courteously, they stopped to allow the Prado to descend ‘the stairs’.

- Inside Ramon Crater.

The rate of his descent of ‘the stairs’ totally alarmed the Border Patrol Officer who was instructing the group.

- Descending “The Stairs”.

He wasn’t aware that the Toyota Prado ‘shopping trolley’ had some tricked up suspension – and an experienced pilot at the wheel!

On exiting the makhtesh Ofer and I drove along Wadi Nekarot, heading to Sapir Pool and then camp. We took time to get a size comparison of the wadi cliffs. (see the following photograph).

- Wadi Nekarot.

SAPIR POOL

After lunch Kerry joined Ran in the F350 and drove to Ein Yahav and then to Sapir swimming pool.

- Sapir Swimming Hole.

- Ehud and Sean, Nimrod and Jonathon.

- Lawn and gardens at Sapir.

- Ehud, Ran, Kim, Ohad.

Ofer and I arrived at Sapir Pool around 4.30 p.m. only to find that the bike crew had been there for some time. This swimming hole at the settlement in the desert, named after Pinhas Sapir, a member of the Knesset who did much to develop the Negev, features an environmental sculptures garden by the Australian artist Andrew Rogers.

Inviting as the pool was, I was the only one who didn’t go for a swim, declaring that I had no desire to swim in ‘liquid duck shit’. Matan left the group after the swim at Sapir Pool to attend to urgent personal business, little knowing that he was soon to return.

Everyone else, bike crew and 4WD crews, returned to Wadi Nekarot. Mechanic extraordinaire Yami and other friends had arrived to share the camp.

- Kerry

DAY THREE – Saturday 22 September 2012

DAY THREE – Saturday 22 September 2012

The camp was awake at 7.00 a.m.

- I suppose it’s morning.

- Ofer and Sean on the ridge above the camp.

The broad plan was for the crew in the Prado to visit Wadi Zin, Wadi Hatzera, the Small Crater and then meet up with the bike crew at Arad.

The bike crew headed off along the ‘spring route’ (same as Day One but in the opposite direction).

TO THE SMALL CRATER

Just after the bikes took off, Ofer, Kerry, the two young boys and I headed off north in the Prado along Route 90, to go to the Small Crater.

Enosh was left at the campsite, with friends who had arrived the previous night, to finish packing the F350.

- Wadi Zin

- Wadi Zin

Along the way we called in at Wadi Zin, a side wadi of the Wadi Arava to the west. Wadi Zin is mentioned in the bible but probably not for the activity for which it is most popular today – abseiling.

It was then on to Hatzera Cave, where, although it was late in the season, Ofer hoped to find some water in the cave. For reasons that are obvious once one sees it, it is also known as Stalactite Cave.

- The approach to the stalactite cave.

- The stalactite cave.

- From the inside of the cave.

- The reason for its name.

Ofer then drove around to the top of the cave to get a different perspective. It was only late morning but the day was already heating up.

- Above the stalactite cave.

- Wadi Hatzera

- Wadi Hatzera from above.

- Above Wadi Hatzera.

We then headed to the Small Crater (Makhtesh Katan, also known as Hatzera crater).

- Into the Hatzera Crater.

- Amazing uplifting of rock.

- Part of the Makhtesh.

- Descending from the small crater.

- In Makhtesh Katan.

- Our road out.

The bike crew crossed Route 90 at Ein Khatseva and powered along Wadi Amatzia (same route as Day One but in the opposite direction).

About ten kilometres down Amatzia they turned left up Hadav wadi, crossed Route 90 again and headed towards the Small Crater (Makhtesh Katan), also known as Hazera crater. It is the easternmost makhtesh and the smallest one (eight kilometres long and six kilometres wide). It is often referred to, and marked on maps, as the Small Crater.

- Ran at Wadi Hatzera.

They were hoping to rendezvous with Offer and I in the Prado. However, they arrived some time after we had left.

The riders headed out of the crater on the access track towards Route 25.

- Ehud and Ran.

- At Nakhal Amatyahu.

They were riding along a short compacted section of the access road when they came to switchback. Nimrod and Ehud, in the lead, negotiated the U turn with ease. Ran slowed dramatically and just made the turn. Ohad, on the outside of the turn, had no chance of slowing and went straight ahead. The others just stared in wonderment as he rode over large boulders, rocks and other obstacles, and came to stop 20 metres from the track, upright and unscathed.

BAD NEWS

In the amazed silence that followed they could hear a number of phones ringing in backpacks. Nimrod took the call. “Bad news. We have to go back”.

Meanwhile, Offer and I had left the Small Crater and headed out along the main access track to Route 25. After ten kilometres, we turned right onto Route 258, heading north, intending to meet the bike crew at Arad. Fifteen kilometres from Arad, Ofer took a phone call. “Bad news. We have to go back”.

ENOSH’S ADVENTURES

After Enosh had packed the F350 he stayed at the campsite, reading, until the flies drove him into action. He left the campsite and drove the big pickup to the dumpster bin near the road (Route 90).

He got out, went to the trailer, threw the garbage into the dumpster and as he turned to get back into the vehicle he noticed the mattresses in the rear were on fire.

Enosh relates what happened:

“I tried to release the web covering the mattresses. I released the ratchet strap but the back of the pickup was already in flames. I pulled four mattresses off the vehicle. By this time all the back was alight. There was too much heat because of the wind.

I went into the cab to get the extinguishers. Got two. I ran to the upwind side and sprayed the fire extinguishers. I ran to the road, stopped a vehicle and got their fire extinguisher. They had no effect. The fire died and re-started.

I am a trained Merchant Marine Officer and I was involved in weekly fire fighting drills. I knew it was too late. I tried to get into the cab to retrieve gear but there was too much heat and smoke to do anything. I turned off the engine and shut the door. I ran back to the road to keep away onlookers because I was worried they were getting too close.

The rear window exploded, then the interior exploded. A column of smoke went about 30 metres into the air. The horn went off, crying like a dying animal.

About 30 minutes after the fire started an ambulance arrived, followed by a small fire truck. The Police arrived and then a larger fire truck but all the crew could do was cool down the remains of The Beast.

I went to hospital suffering from smoke inhalation and heat radiation but was released after six hours.”

- Kim with remains of radiator.

- The devastation caused by the blaze was total.

- The result of intense heat.

- Ofer contemplates what once was.

- Lots of personal items were destroyed.

The drama was not yet over. The rear wheelbearing on Nimrod’s bike gave out. Offer and I in the Prado met him at Ein Hatseva fuel station and left him there to await pick up later. Ehud had continued onto Ein Yahev and the burnt-out F350.

Ran and Ohad were riding together back to Ein Yahav but as they had no insurance they could not ride on the bitumen and had to use tracks paralleling the highway.

Some hours after an explanatory phone call Matan arrived at Moshav Ein Yahav (with his girlfriend – perhaps that was what the urgent personal business was) to help transport the bikes back to Hod HaSharon. It is good to have friends one can rely on.

The Beast was replaced with a shiny new 2012 model.

- Replacement.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Bike Preparation

Enosh Aroet

Ran Daggan

Kerry Davies

Ohad Fridman

Matan Genosar

Ehud Powitzer

Nimrod Powitzer

Ofer Powitzer

Navigation

Ofer Powitzer

Nimrod Powitzer

Photographs

Ran Daggan

Kim Epton

Ohad Fridman

Nimrod Powitzer

Maps

Nimrod Powitzer

Clarification of the Route

Ofer Powitzer

Nimrod Powitzer

Text and Layout

Kim Epton

© Kim Epton 2025

4359 words, 147 photographs, four images.

Feel free to use any part of this document but please do the right thing and give attribution to adventures.net.au. It will enhance the SEO of your website/blog and Adventures.

See Terms of Use.