Into the Great Victoria Desert

We left Norseman with full tanks, heading north-east on the Eyre Highway. At Fraser Range it was a sign of the times that the leaseholders had locked the gates at the three possible access points to the Fraser Range-Zanthus Track. While we could have visited the homestead to arrange access it was all too hard and too far away so we continued to Balladonia from where we would take the Balladonia-Zanthus Track.

Whenever travelling the Eyre Highway I try to avoid the outrageous fuel prices at Balladonia but on this occasion we had no option but to top up. We found a campsite at Afghan Rock.

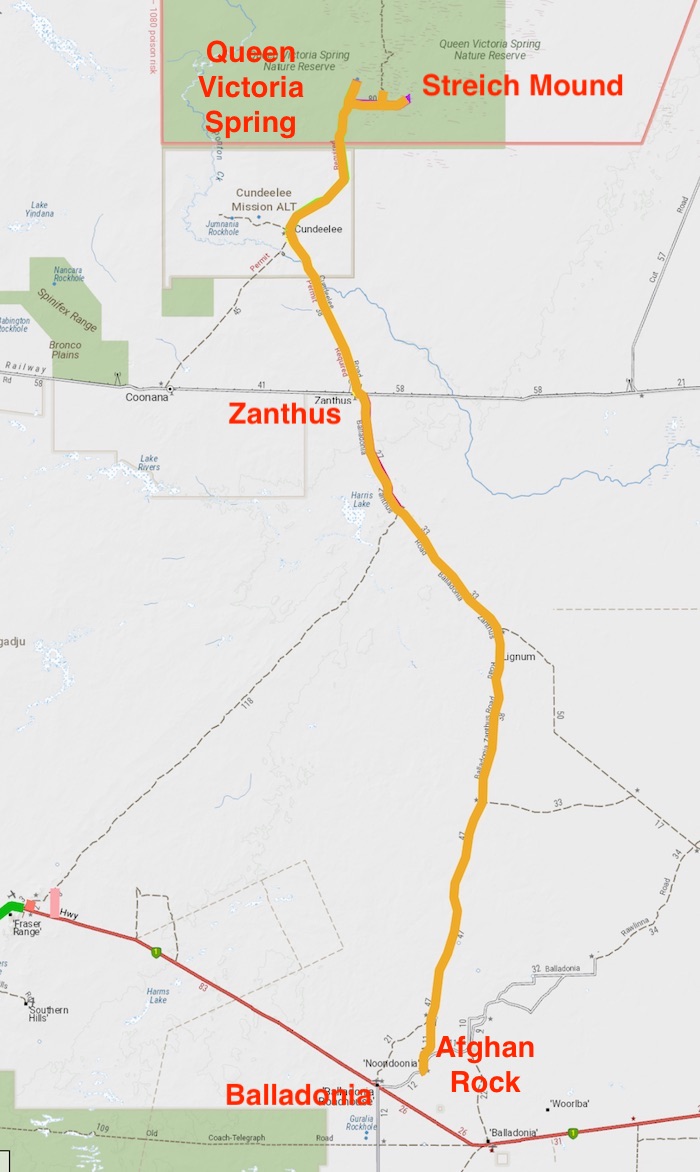

Afghan Rock to near Queen Victoria Spring, Great Victoria Desert

- ROUTE OF DAY 4

The southern portion of the Balladonia-Zanthus Track is very sandy and deeply rutted. A standard dual cab 4WD ute would have difficulties maintaining forward momentum and even staying on the track. The deep ruts took control of the steering, the dirt was scraping the underbody and driving safely was a challenge.

Further north there were numerous shotlines on both sides of the track. There was evidence of exploration activity all around. IGO Exploration is searching for nickel.

- Remains of bore sampling. It would appear that IGO are searching for nickel.

- Each of the shotlines was named.

Lightning strikes had caused numerous fires and much of the country was burnt out.

- A very dry Car Bob Dam on the Balladonia-Zanthus Track.

- Brad and Jane arriving at New Pioneer Tank on the Balladonia-Zanthus Track.

We met James and Tim at Zanthus.

This siding on the Trans Australia Railway was opened in 1917. The name is derived from the latter part of the genus name for the Kangaroo Paw – AnigoZANTHUS. The railway from Port Augusta to Kalgoorlie opened in 1917 and was Australia’s first major infrastructure project. Western Australia had made the construction of a railway linking the nation’s eastern and western colonies a condition for joining the Commonwealth in 1901.

The track north out of Zanthus was in reasonable condition until we reached Ponton Creek. Substantial flow in the Ponton Creek used to cut access to the Cundeelee settlement and while it was not the main reason for abandonment of the settlement, it was a contributing factor.

- Aaron takes his Nissan Patrol across Ponton Creek.

- Mushy and Ray in the Navara at Ponton Creek.

- Santokh in his Prado at Ponton Creek.

- Paul and Andrew in the Pajero at Ponton Creek.

- James and Tim in the Wrangler at Ponton Creek

- Brad and Jane in the Troopy at Ponton Creek.

- James checks out a wrecked truck in Ponton Creek.

A ration depot was established in the area in 1939. Cundeelee mission and school was opened by the Australian Aborigines’ Evangelical Mission in 1949. It was run by inter-denominational churches until 1982, when it became an Aboriginal Community.

- Derelict buildings at Cundeelee.

- Cundeelee detritus.

Many of those at Cundeelee were Tjuntjuntjuara people from the Great Victoria Desert near Maralinga who had been relocated while the British Government was testing atomic weapons in the 1950s. These ‘Spinifex People’ were unhappy at Cundeelee and the majority moved back to their homelands in the Great Victoria Desert in 1984-86.

The original name of Cundeelee is Urpulurpulila – ‘tadpole’ in Pitjantjatjarra language – from the large number of tadpoles found in the rock hole there.

- International pickup truck just north of Cundeelee.

It took some time to determine the correct track north out of Cundeelee to Queen Victoria Spring.

Ernest Giles and his exploration party of six had travelled with camels more than 520 kilometres from Boundary Dam (on the WA/SA border) without finding any water when they lucked upon this spring.

Late in the evening of 25 September 1875 Jess Young was navigating and was steering about 20 degrees off course. Giles had to intervene and correct the heading. Had he not done so the explorers would have passed three kilometres to the north of the water.

Whether foolhardy, brave, lucky or calculated the discovery of what is now known as Queen Victoria Spring certainly saved Giles’s party.

A major fire in May 2019 has totally devastated the Queen Victoria Springs Nature Reserve. It will be many years before it recovers.

- Most of the Nature Reserve was burnt out in May 2019.

- A very dry Queen Victoria Spring.

- Kim and James walking to the marker.

A tree was blazed by the Elder Exploring Expedition in 1891, 200 metres south of the pool. Today there is an inscribed plaque on a concrete post and nearby a ground marker where the tree once stood.

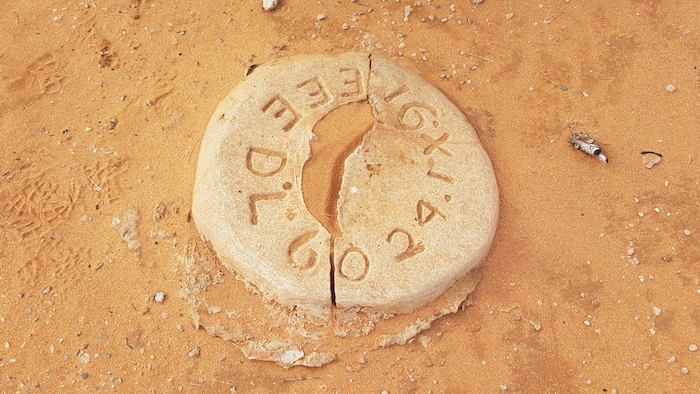

- 1891 Elder Expedition marker.

- Concrete marker at Queen Victoria Spring.

This plaque is engraved “E.E.E. D.C.L. 60 23.9.91” and was placed there by the grandsons of Victor Streich, the geologist on the expedition.

We left Queen Victoria Spring, heading for Streich Mound.

- Marker column on Streich Mound. Dark clouds herald the approach of a storm.

- James, Tim, Jane and Paul on Streich Mound.

- Streich Mound Marker

- Vehicles parked below Streich Mound.

Attempts to drive to the top of the Mound were unsuccessful and we settled on the ‘carpark’ partway up.

We left Streich Mound searching for a campsite. Everything on offer was burnt out. We passed the occasional patches of vegetation but no suitable campsites presented. The passage of time forced us to select a barely adequate campsite – its main attribute being a reasonable supply of wood.

The pelting rain soon passed and we made a comfortable camp.

Near Queen Victoria Spring to Great Victoria Desert

- ROUTE OF DAY 5

- Monday’s camp on Tuesday morning.

Our camp was less than 100 metres from a break in the dunes – the reason the track was routed where it was. As the track wound its way north this method was used more and more. There were deviations of up to two kilometres to get around the end of dunes running east-west. The track would then be routed in the swale until the next break was found. About 32 kilometres after leaving camp we arrived at Argus Corner and turned right onto the Nippon Highway.

- At Angus Corner. The freshness of the sign belies the remoteness of the location.

After we passed Lindsay Lake, 25 kilometres north-east, there were numerous shotlines and other signs of mineral exploration.

- The call up protocol is designed to make travellers aware of other vehicles on the track.

A Japanese corporation, Power Reactor and Nuclear Fuel Development Corporation (PNC), explored for uranium here in the 1970s. It is now run by Vimy Resources as their Mulga Rock Project. It is Australia’s largest advanced uranium project with an estimated 15 year production life. The further north, the more signs of exploration activity.

- We stopped for a break at this water point.

- More about preserving a modern mining company operating in an onerous compliance environment.

The name of the track on which were travelling – Nippon Highway – and the one to which we were heading – PNC Baseline – were derived from the Japanese activity in the 1970s.

- At the intersection of Nippon Highway and PNC Baseline, close to the Vimy Resources Mining Camp.

Vimy’s camp did not appear to be in operation and a locked gate across the track 22 kilometres north east added weight to that assumption. The arrogance of placing a gate across a public road with no advance warning is breathtaking. With only enough fuel to get to Laverton we had no option but to proceed forward. We couldn’t find the combination to the lock (we didn’t try the phone number reversed) and we didn’t want to interfere with the gate so Mushy found a way around it. Eight vehicles later it was a defined track.

Sixteen kilometres further along we came across the Tropicana Haul Road – a veritable highway leading to the Tropicana Mine 220 kilometres north-east of Kalgoorlie. This road provides easy access to Vimy’s camp which may have been part of the reason for the gate across the PNC Baseline.

- The ‘Tropicana Highway’ with the sign pointing to the way we had come.

- Intersection of the Tropicana Highway and the PNC Baseline.

At the Tropicana Highway we had to again pick up the PNC Baseline. The roadworks did not make this easy. Mushy put up his drone and soon located a track. It appeared that a vehicle or two had been along the track reasonably recently (possibly early August from the info left in the visitors’ book at Queen Victoria Spring), however, not many other vehicles had been on the track for many years. It was very overgrown and damaged the fittings on our vehicles. It was to be 25 kilometres before it opened out.

- Convoy in thick bush.

The PNC Baseline approached Lake Minigwal and we stopped for lunch at the intersection with an un-named road skirting the lake to the east. Lake Minigwal trends from the north-west to the south-east for about 67 kilometres. It contains numerous islands. It was originally named ‘Ainslie Fairbairn Lake’ by Frank Hann in 1907 after one of his friends but the name was never shown on maps.

In 1935 Donald MacKay, the leader of the MacKay Aerial Survey Expedition, named it Lake Minigwal after an aboriginal word for woodspear.

- Lunch at Lake Minigwal.

We were skirting Lake Minigwal to the east.

- Dromedary Junction. The Ethel Hill referred to is about 11 km to the east-south-east.

- On the way to Surprise Granite Rockhole.

Eight kilometres further on we turned into Surprise Granite Rockhole. These were named by that indefatigable explorer Frank Hann in 1907 but he did not state why he was surprised.

- Santokh at Surprise Granite Rockholes.

- Steve, Santokh, Andrew and Tim at Surprise Granite Rockhole.

- Surprise Granite Rockhole.

- Steve at Surprise Granite Rockholes.

Unprepossessing Hanns Jasper Hill, close to the difficult-to-see Stella Range and the not-seen Lightfoot Lake, was a bit of a disappointment. We didn’t go to nearby Granite Hill either.

- Burnt out country near camp.

Our camp this day was off the track just beyond the northern extremity of Lake Minigwal.

- Aerial view from our camp near the northern end of Lake Minigwal.

We were nearing the end of our desert visit and tomorrow we would be heading to Laverton and a tour of the north-eastern and northern goldfields.

Go back to Dunn Track

© Kim Epton 2024

1734 words, 40 photographs, two images.

Photographs

Kim Epton

Jane Dooley

James Hay

Michael Orr

Ray Dowinton

Feel free to use any part of this document but please do the right thing and give attribution to adventures.net.au. It will enhance the SEO of your website/blog and Adventures.

See Terms of Use.